Written for my 20th century Design Class in 2020. Assignment was to write an article about modernism in Australia from the editorial perspective of an architectural publication in the 1970s.

Modern Australia

’Modernist design for a modern way of life in the office’

We are living in a new age, an age of modernism that is shaping how we work into the future and invigorating Melbourne’s workplaces for the modern company. Design is all around us: magazines, furniture, art,and everyday objects. Design has played a significant role in how buildings are transformed to improve the way we work and use space. Australian designers and architects, by circumstance of World War Two, were able to bring functionalism and modernism to their fields and ultimately influence changes in Melbourne’s office buildings with the opening of structures such as the ICI building in 1958 by Bates Smart & McCutcheon bringing an international flavour to Melbourne.

Modernism had a complex existence at the start of the 20th century and as we close out this decade, we are now seeing how it is influencing design in our country and building utopia. The influence of modernism is widespread with its interdisciplinary approach across art, design, and architecture. Modernism evokes the spirit of the times and solving everyday problems with design. We have seen mass production take advantage with smart design, aesthetic and form follows function. Grant Featherston’s curl chair shows us how these principles are applied to design a chair that represents domestic relaxation and comfort with moulded plywood chairs that formed around the human body. Featherston’s thinking also expanded into the corporate world as ICI house featured furniture from his collection. Modernism is transforming Melbourne into a complex metropolis and offering access to new and exciting ideas.

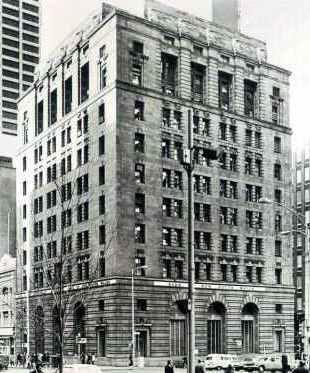

Prior to World War II – ‘interwar’ Melbourne saw a period of styles that included Art-Deco, Moderne, Functionalist, Chicagoesque and Commercial Palazzo; and committee restrictions impacted on the height of buildings that were able to be constructed. This interwar period was possibly Melbourne’s finest period of development coming out of the Great Depression, creating a beautiful city that filled out uniformly. APA Tower in Collins Street ruled the Melbourne skyline for decades at 14 storeys high (76metres to tower pinnacle) fringed the limits that were in place since 1916. Melbourne was ready to break through these restrictions, had just been on the international stage through the 1956 Olympics, we were optimistic to be a modern city.

Australia’s involvement in World War II through the Pacific campaign saw innovation in design techniques and materials used. The Engineers Headquarters of the US Army was setup in Melbourne, Osborn McCutcheon from Bates Smart & McCutcheon was appointed the Chief Architect of the Architectural Section. Architects from across Melbourne started to join the cohort all wanting to play a part in the war effort. The collective group of architects and army engineers proved to be successful in acquiring knowledge necessary to complete work for camps, hospitals, airport buildings and more. Innovation produced improved construction methods, structural experimentation, and architectural practice; this played an important part in shaping Australian architecture towards the end of the 1950s. Even though World War II ended in 1945, it took a decade for Australia to really break through and make headway in the Architectural world with a shortage of materials and investment, but we were not short on ideas.

Osborn McCutcheon, a director at Bates Smart & McCutcheon was pivotal in reinventing Melbourne’s skyline to develop into a modern international city. McCutcheon studied architecture at Melbourne University from 1919-21 before working for firms in San Francisco and London from 1922-25 and then travelling Europe. A ground-breaking project for the firm that was driven by Osborn sustained the firm during the depression was the commercial palazzo-inspired AMP Building in Melbourne, completed in 1932 which was a minimal design in its decoration. The building also featured a concealed panel heating system. McCutcheon was already showing that he could be innovative early in his career.

We have already written of war time and McCutcheon and his role as Chief Architect, it was a revelation for McCutcheon to be amongst the coordination of specialised teams that developed repetitive building systems,programs of mobilisation, prefabrication and efficient techniques of delivery. At the end of his service, McCutcheon returned to private practice and travelled to the United States, England and Europe to observe how the rest of the world was moving on post World War II with projects in New York – Wallace Harrison’s United Nations Building (1952) and Gordan Bunshaft’s Lever House (1952). Upon his return to Melbourne and Bates Smart & McCutcheon they initiated studies into lightweight construction techniques alongside the experiences they gained during World War II. The firm stood up multi-disciplinary teams of architects, structural engineers, services, estimating, interior design, accounting, and general clerical. Early principles were applied to various projects across Australia with six MLC buildings. But it was not until the ICI Building in Melbourne that launched modernist a skyline in Australia.

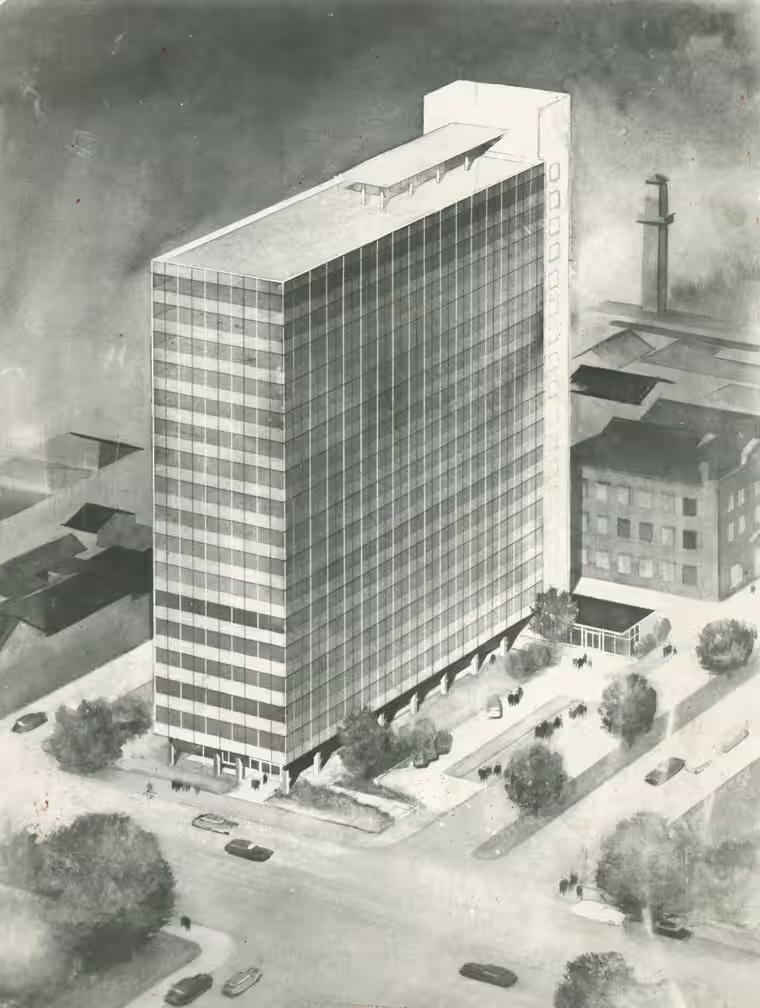

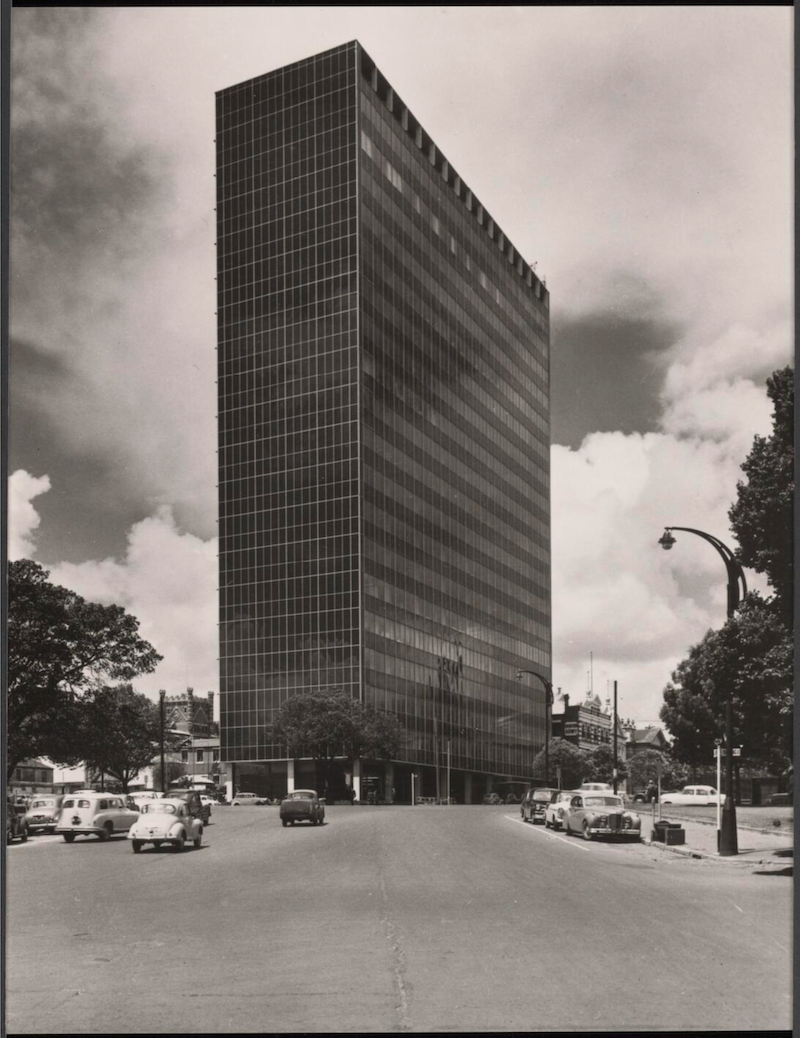

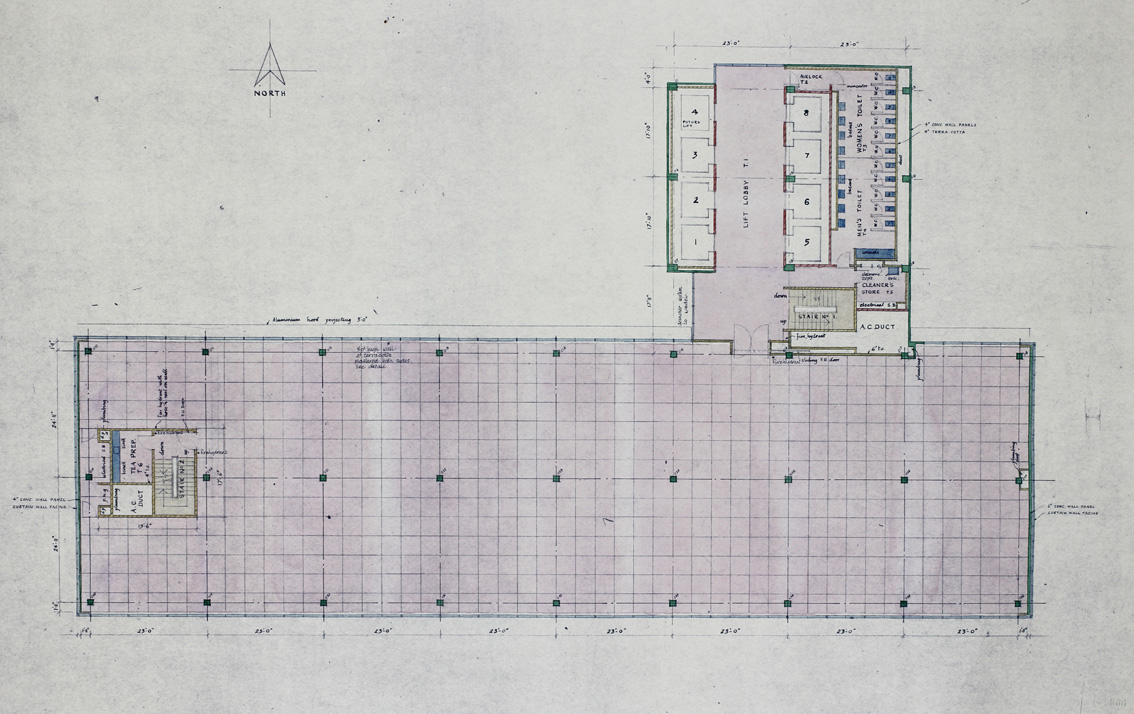

Australia’s first skyscraper was rejecting history and conservative values, with innovation and experimentation of form and function and an emphasis on materials. A curtain wall & metal, glass-box design with open plan layouts, modern amenities and furniture, ICI House was permitted to break height limits. McCutcheon proposed a slimmer vertical stacked footprint and incorporatinga garden to create a beautiful public space at street level. Robin Boyd, a popular voice of architecture opinion was supporting the cause with his opinion pieces in The Herald: “This is a clean, precipitous tower in the best tradition. Elbow room is the first essential for effective skyscraping, and the ICI has that.” (Haigh, 2016).

As height was the obvious feature and most talked about topic of the project, an anxious Melbourne Fire Brigade was worried that their ladders could not reach, but McCutcheon had countered their worries with an innovative pioneered sprinkler system from the fifth floor and above for fire protection. Inside and out, the tower was fashionable. Covered in gleaming glass curtain walls on both north and south that floods the interior with natural light, ICI House is a tribute to McCutcheon’s visits to the New York Lever House and UN Building.

Within, we are presented with continuous space, a ground-breaking open plan that would incorporate ‘Bürolandschaft’ – an planning concept based on open-plan offices out of Germany from the 1950s free from partitions, large spaces could be designed to be respectably serviced and lit. The building was able to achieve this by isolating building services like lifts, plumbing and air conditioning into a 275-foot service tower.

ICI House was the envy of many companies and multinationals for its new office space in Melbourne. When ICI House opened, in his speech ICI Chairman Fleck spoke “the buildings they commission shall be not only appropriate to their needs and efficient, but also aesthetically satisfying”.

With air-conditioning and sealed windows, the building was a relief for workers during Australian blistering summers keeping the building at a constant 20C. With access to a rooftop garden, 400-seat cafeteria with a coffee machine, basement amenities and uninterrupted views across Melbourne in all directions ICI House was an Australian landmark for a modern workplace and the race was on for one-upmanship in Sydney when in 1962 the title went to AMP Society for Australia’s tallest building.

The tower also symbolises Australia’s contribution to the Modernism movement, demonstrated by overseas architects such as Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) One Chase Manhattan Plaza (1961). Allocating most of the site’s footprint to an elevated public space – just as ICI House had with its public entrance garden. One Chase Manhattan Plaza stands improbably thin. Bunshaft set the building’s steel beams on its exterior, clad with glass and aluminium. Mies van der Rohe’s first attempt at a skyscraper Seagram Building (1959) also in New York embodies the principles of modernism also provided public space, setting back the building 100 feet from the street which created an active plaza with two large fountains with generous outdoor seating. As van der Rohe is considered the cornerstone of “The International Style” he bought the modernist movement to the world through his earlier designs – Farnsworth House (1951) and Crown Hall (1956).

The curtainwall & glass style was becoming a trend with other projects popping up in Melbourne not that long after ICI House opened. The second building with a full glazed multi-storey curtain-wall façade with full transparency was Coats House (1959) at the top end of Collins Street. As well as the Bank of Adelaide building further down Collins Street, with asymmetrical glass curtain-wall design with significant offset curtainwall to rest of the building which showed off the building’s stair well. And the most recent addition to Melbourne’s skyline is the elegant black-steel structure and bronze TAA Headquarters (1965) in Franklin Street is architects Harry Norris & Partners most prominent and accessible work.

Melbourne is now in a position to loudly declare to the world and Australia ‘We are a modern city!’; and we can provide that multinationals can provide their employees a innovative place to work and a place to build their new Australian headquarters. We are a modernist city that is ready to reject conservative views and look past the history of this city and build new utopian city with aesthetically designed buildings that will soar up into the sky as they do in other popular metropolis such as New York City and Chicago. It is time to catch up.

Bibliography

- Philip Goad & Julie Willis (2003) Invention from War: a circumstantial modernism for Australian architecture, The Journal of Architecture, 8:1, 41-62;

- Wilk, C. (2006). Introduction: what was Modernism? In C. Wilk (Eds.), Modernism: designing a new world: 1914–1939 (pp. 10–21). London: V&A Publications.

- National Trust of Australia (Victoria) (2014). Melbourne’s Marvellous Modernism, A comparative Analysis of Post-War Modern Architecture in Melbourne’s CBD 1955-1975

- Haigh, Gideon (2016). Melbourne’s bold leap upwards: the inside story of Australia’s first skyscraper. The Guardian.

- Huppatz,D. (2017). Mid-Century Modern: Australian Furniture Design.

- Bates Smart. (2018). 165 Years of Enduring Architecture.

- Sievers, Wolfgang. (1958). ICI House, East Melbourne, 1958-1959 Retrieved May 22, 2020, from National Library of Australia

- Berry, Louise. (2018). Bürolandschaft: how the way we work has shaped the office.

- Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. (n.d) One Chase Manhattan Plaza.

- Perez, Adelyn. (2010). AD Classics: Seagram Building / Mies van der Rohe.